Understanding digital evidence in Malaysian courts

By Anushia Kandasivam October 11, 2016

- Malaysian law uses a wide definition of electronic evidence

- Conditions of admissibility must be satisfied

.jpg)

MALAYSIA amended its statute on evidence in 1993 to incorporate a section on electronic evidence. This update in the law came rather later than those in fellow Commonwealth countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom, where most additions to current law dealing with technology were incorporated in the 1970s and 1980s.

Nevertheless, section 90A of the Evidence Act 1950 is what governs Malaysia in terms of electronic or digital evidence and its admissibility. The definitions under and nuances of this section were explained by Mariette Peters (pic, above), a partner of local law firm Zul Rafique & Partners, to an audience of internal auditors at the Institute of Internal Auditors National Conference 2016 on Oct 10.

Peters explained that in the legal profession and among the judiciary, the words ‘electronic evidence’, ‘digital evidence’, ‘computer evidence’ and several other similar terms are used interchangeably. However, they all refer to the same legal definition in the Act – basically “a document produced by a computer.”

“The reason Parliament incorporated this section into the Act is because they wanted to bring the law up to date with the realities of technology,” she explained.

The maker of the statement

In a courtroom, the general rule is that the maker of the statement must be called to give evidence. For example, if a witness says, “Mr A told me that…”, this is considered hearsay as the original maker of the statement is not present. Mr A himself should be present and giving evidence in court.

When it comes to electronic evidence, section 90A allows the computer itself to be the maker of the statement and overcomes the hearsay rule.

What is a document?

The definition of ‘document’ in the Act is extremely expansive. “It covers almost anything. It would be easier to ask what isn’t a document,” says Peters.

According to section 90A, a document can be any matter expressed upon any substance. This includes letters, figures, symbols and other forms of expression on any material ranging from paper, tape, film, stone and wood to visual or audio recordings and electronic impulses.

Peters illustrated this with an example of a case where a woman who was stabbed spelt out the name of her attacker on a wall before she died. This was admitted as evidence of the identity of her murderer and the wall was a document under the definition of the law.

“A document does not have to be anything in hardcopy; it can be a display as well,” clarified Peters.

The case of PP v Ahmad Najib Aris, more famously known in Malaysia as the Canny Ong murder trial illustrates this point – in this case, CCTV tape was used as evidence of the accused kidnapping the victim, with the tape clearly falling within the definition of ‘document’.

What is a computer?

“When most people think of a computer, they think of a desktop or laptop, but the legal definition in the Act is again very wide,” pointed out Peters.

The Act defines a computer as a device that performs ‘logical, arithmetic, storage and display functions, and includes any data storage facility or communications facility’.

Under the law, a computer can include a ticket vending machine and a smartphone. Peters referred to Hanafi Mat Hassan v PP to explain. In this case, where the driver of a public bus was accused of the rape and murder of one of his passengers, the victim’s ticket was used to establish that she was on the bus at the same time as the accused (the ticket being the document) and the ticket vending machine fell under the definition of ‘computer’ according to the law.

Digital evidence

Peters explained that judicial interpretations of ‘document produced by a computer’ have included bank statements, lists of car registrations from the department of motor vehicles and computerised results of DNA profiling and caller or SMS ID reports.

This last example was illustrated in two infamous Malaysian murder trials - PP v Azilah and Sirul, (the Altantuya murder trial) and Pathmanabhan Nalliannen v PP (the Sosilawati murder trial). In these two case, SMS logs were used as evidence.

“Once we have established that it is a document produced by a computer, we have to show that the document was produced by the computer in the course of its ordinary use,” continued Peters.

This condition must be satisfied before the document can be accepted as electronic evidence, she explained.

To establish that the document was produced in the course of the computer’s ordinary use, a certificate signed by the person who is ‘responsible for the management of the operation of that computer’ may be produced.

This person can be someone in an establishment with an information technology background. For example, the Malaysian courts have accepted a certificate signed by a company’s electronic data processing manager.

Takeaways

At the end of the session, Peters summed up three important points to note about electronic evidence:

First, by law it is a document produced by a computer. Second, this definition covers almost everything. Third, for it to be admissible in court, there needs to be a certificate drafted by someone with knowledge of how the document was produced or the person with knowledge of how it was produced should come to court to explain how it was produced.

Related Stories:

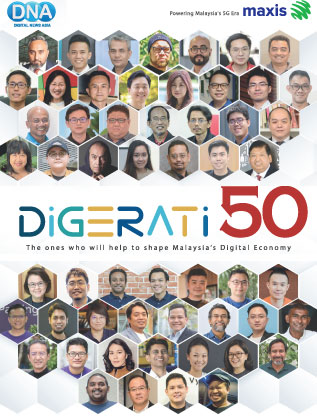

Digerati50: The legal eagle techie

MaGIC publishes legal handbook for social enterprises

Singapore’s Lawr.co launches in India

For more technology news and the latest updates, follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn or Like us on Facebook.